The Chilling Story Of Juan Severino Mallari, Philippines’ First Serial Killer

There was more than meets the eye in the sleepy town of Magalang, Pampanga, at the turn of the 19th century. Something mysterious was terrorizing the place, and townspeople were not at ease.

And who would be when 57 locals were murdered in a decade—all linked to one heartless killer?

When the culprit finally revealed himself, he was neither a poor indio who murdered for financial gain nor a random Jack The Ripper who fancied slashing throats.

To everyone’s surprise, the killer was none other than their curra parroco (parish priest)—a Filipino named Juan Severino Mallari.

When the murders took place, discrimination against Filipino priests by the colonial authorities was rampant. So, you can only imagine how the Spaniards reacted upon hearing the horrible news. Ending one person’s life by accident may have been forgivable, but slaughtering 57 people was as shocking then as it is now.

By definition, a serial killer is someone who “commits more than three murders over a period that spans more than one month.” But the case of Father Mallari is unique: He committed the crimes long before the phrase “serial killer” was even widely used.

Based on scanty records available, Mallari’s early years indicated no violent tendencies. According to Dr. Luciano P.R. Santiago, author of Laying the Foundations: Kapampangan Pioneers in the Philippine Church 1592-2001, the Filipino priest came from a Kapampangan family whose ancestors were the benefactors of their local church.

Soon after taking up philosophy and theology at the University of Santo Tomas, Mallari became a priest. He was ordained in 1809 and later served as the coadjutor of Gapang, Lubao, and Bacolor.

As a man of ambition, Mallari tried to become a parish priest three consecutive times: first, in Orani; then in Mariveles, Bataan; and, finally, in Lubao. Although he was shortlisted in all attempts, Mallari didn’t get the job.

He also applied for the sacristanship of the port of Cavite, but this, too, ended in rejection.

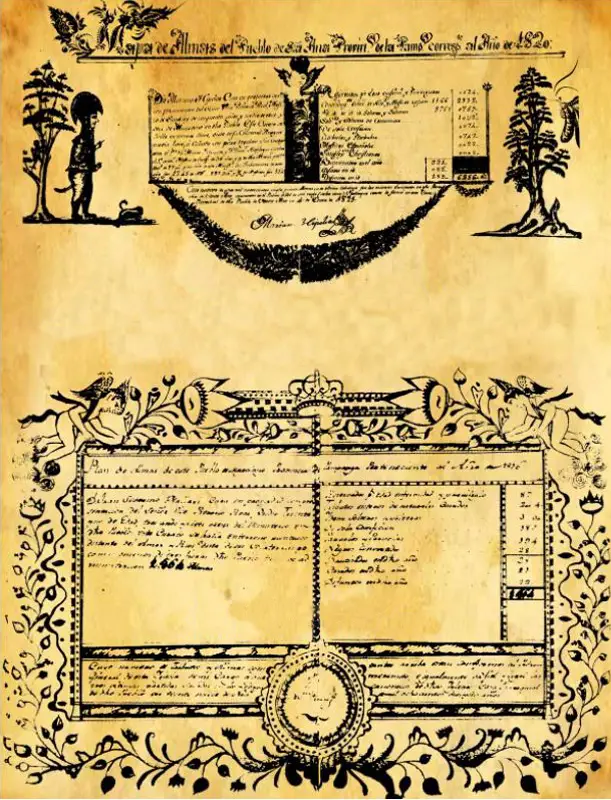

But opportunity favors the persistent: Mallari finally won the pastorship of San Bartolome Parish in Magalang, Pampanga, in 1812. During his term at the local church, he showed his creative side. A self-taught calligraphy artist, Mallari would often escape the lethargy of his job by decorating his annual reports (also known as Planes de Almas) with drawings of flowery vines and naked boy angels.

Mallari’s art was way ahead of his time. He was the second Filipino priest in history who was also a calligraphy artist, following the footsteps of another Kapampangan—Father Mariano Hipolito. Mallari’s impressive drawings (now stored at the Archives of Archdiocese in Manila) are even older than the first art academy in the Philippines, Academia de Dibujo, established in 1823.

But despite his success and religious faith, Mallari still had to battle his demons. He suddenly became mentally unstable—so much so that he had to be replaced by a cura substituto in 1826. The same state of mind led him to kill 57 parishioners because he “believed that he could by this means save his mother who, he had persuaded himself, had been bewitched.”

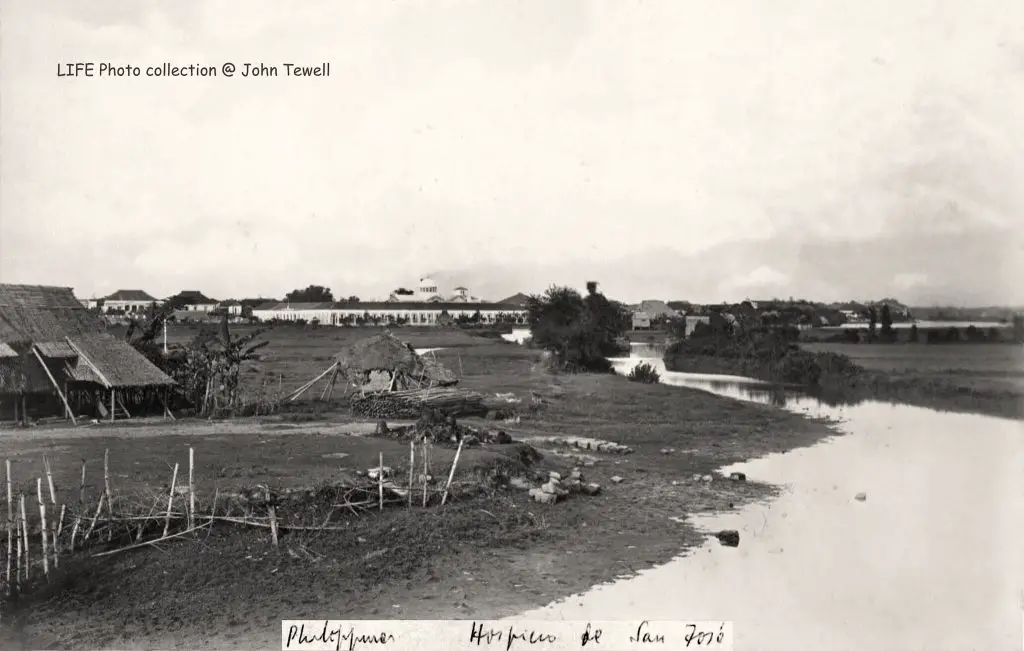

Information about his mother’s condition and how Mallari’s victims were slain is nonexistent, but one thing was evident—the Filipino priest was not in the right frame of mind. However, the Spanish authorities were probably aghast by the sheer casualty count that they didn’t even think of putting Mallari in a mental institution like the Hospicio de San Jose, established in 1810 and considered the country’s first psychiatric hospital.

Ultimately, Mallari was brought to Manila, where he suffered behind bars for several years before his execution by hanging in 1840. Although relatively a footnote to Philippine history compared to the GOMBURZA, Mallari was the first Filipino priest to receive the death penalty and possibly the first to be a victim of injustice.

His death at the hands of the Spaniards only reinforced the colonizers’ perception that Filipinos were ignorant people who believed in many superstitions.

In Volume 40 of Blair & Robertson’s The Philippine Islands, where the life of the ill-fated Mallari is briefly mentioned, Spanish chronicler Sinibaldo de Mas called the Filipinos’ belief of unexplained beings and phenomena a “mental weakness.”

Regarding Father Mallari, he said that the “attorney on that case talked in pathetic terms of the indescribable and barbarous prodigality of blood shed by that monster” and even tried to make sense of the events by linking them to the “natural timorousness” of the Indio.

Although more research is required to uncover specific details surrounding Father Mallari’s tragic life and death, this story proves that history is often more terrifying than any horror movie.

References

Blair, E. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803; explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century; [Vol. 40] (p. 224).

Mallari, J. The Lost Art of Calligraphy. Singsing, 5(1), 107.

Ramsland, K. (2013). Defining ‘Serial Killer’: So Much Confusion. Psychology Today. Retrieved 13 December 2015

Santiago, L. (2002). Laying the Foundations: Kapampangan Pioneers in the Philippine Church 1592-2001 (pp. 60-67). Angeles City, Philippines: The Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel Univeristy.

Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito E. Batongbakal Jr. is the founder, editor, and chief content strategist of FilipiKnow, a leading online portal for free educational, Filipino-centric content. His curiosity and passion for learning have helped millions of Filipinos around the world get access to free insightful and practical information at the touch of their fingertips. With him at the helm, FilipiKnow has won numerous awards including the Top 10 Emerging Influential Blogs 2013, the 2015 Globe Tatt Awards, and the 2015 Philippine Bloggys Awards.

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net